The rest of the conversation at the Jenny that afternoon was forgettable. Most of our conversations were, of course, but that was because they were meant to be – a panacea, a cure-all to get you through the days, the hours. This time though my head was too fired-up by the idea of the Sankey competition for me to be able to enjoy the badinage: all I wanted to do was go back to my room and start scribbling. I managed to resist the urge with the aid of more beer, some of Eric’s best steak-and-ale pie and a huddle of German backpackers, chewing the fat in all senses right up to closing time. But even so, I still barely slept that night, my head teeming with stories and characters, plots and dialogues, situations and dreams – some that were new to me, but quite a few remembered or half-remembered from things I’d written, or started writing, long before.

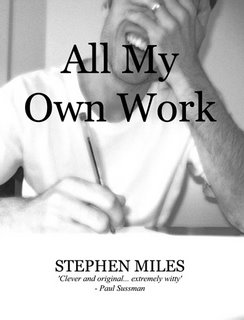

The past year had been the longest period I’d ever gone without writing since I first discovered I could write. I date this life-defining moment to the age of eight, when I won a school prize for a story about a small boy who climbed a mountain. It’s tempting to say it was all downhill from there but although it always brought me more trouble than money, writing was the one constant in my life, the only thing I ever really knew for sure about myself. It started out as the one thing I was any good at in school, and by the time I left it was all I wanted to do for a living. I’ve followed it (and it was always several steps ahead of me) with varying degrees of enthusiasm for most of my thirty-six years at the expense of any kind of career and several relationships, and in spite of my family’s frustration. Having fought for generations a kind of crusade to prove Napoleon was right about the English being a nation of shopkeepers, Mum and Dad had hoped I would follow suit and ultimately take over the family grocers, a small but important local store in the Surrey village where I grew up. It was a disappointment to them at first when I developed no taste for the business, but they got over it; some of the other things I’ve done they’ve found less easy to forgive.

Anyway, thus far, all I’d scribbled at the Dungarry Inn were greetings to new guests on sheets of recycled card saying things like,

GOOD MORNING, HELGA! HERE IS YOUR BREAKFAST. PLEASE LET STEPHEN OR GEORGE KNOW IF THERE’S ANYTHING ELSE YOU’D LIKE. ENJOY YOUR DAY!

which were placed on trays with bowls of muesli, rolls, bananas and yoghurts on a counter at one end of the dining room. I sometimes thought of myself then as an ex‑writer, in the way you might call yourself an ex-junkie: not just someone defined by what they used to be rather than what they were, but literally a kind of recovering addict – in my case, one who’d gone cold turkey, shaken off a dangerous habit and was determined to stay off. This was no more evident than from waking up the day after reading about Sankey with a complete and finished idea for a novel I could enter into the competition, and not only not having a pen or paper to write it down with, but not looking for any.

That said, now that I think about it, that analogy of being a drug addict didn’t quite fit my personal condition: I don’t have any experience of real cold turkey – the occasional attempt at giving up smoking excepted – but it goes without saying that it’s excruciating; by contrast, when I stopped writing I didn’t feel a thing. I was too numb to feel anything at all after what happened with Fon, my wife.

Writing was such a constant feature in my life, and I was so stubborn about it and such a loner in general, that I never expected to get married at all, not just because I didn’t think I’d ever find a woman willing to put up with me but because it basically didn’t seem fair, let alone sensible, to inflict myself on someone till death us did part. I had high expectations of everything, I was impatient, moody and sensitive, and I liked my independence and my own space. But I also knew a good deal when I saw one, and deals like Fon don’t come along more than once in a lifetime.

Of course she was more than a deal, she was more than the sum of her parts, and believe me her parts alone were wonderful. It could be that I romanticise it all out of proportion, but increasingly now I think that what we had was as close to perfection as any of us are ever likely to get. Given my faults and shortcomings, I used to wonder what she saw in me, but then I’d tell myself that that wasn’t my concern; it was a question you should never have to ask. Love doesn’t bear much analysis – thankfully; we’d all be in trouble if it did. It was enough that she loved me and I loved her; nobody has a right to ask for more.

The trouble is, I did. I was the Oliver Twist of relationships. I was always asking for what they couldn’t give me without realising that at worst, that was all you had, and if you had it then you were very lucky, and at best, what they did offer was more than enough for anyone if you knew what you were doing. But who does know what they’re doing in the war between the man and the woman? Not me, that’s for sure.

I didn’t ask for more in the sense of being unfaithful; I did have fleeting pangs for other women every now and then, but they were mostly abstract – faces I passed in the street whom I’d never see again, models in magazines, the occasional dimpled newsreader – and even when they were actually within reach, I was always able to keep those fantasies in my head where they belonged and not confuse a passing crush with real love. I used to think these feelings came from being a romantic, but in my marriage I wasn’t nearly romantic enough; if only I could have saved for my wife some of the intensity and passion I felt for those abstract women, or even for some of the stories I wrote, we might still be together. No: I was faithful to my wife. But it was still due to my betrayal of her that our relationship fell apart.

*

It was a mixed blessing that it was my rota day: with everything playing on my mind, I would have been lousy company for my various friends and colleagues, but being alone meant I had more of an opportunity to dwell on it all. Traditionally on my day off I had an extended breakfast and read the paper from front to back; that morning I had two breakfasts, read a second paper and smoked half my daily quota of cigarettes all before ten o’clock, but it was clear that neither the good ideas nor the bad memories were going away without a fight. The rain wasn’t too bad by Dungarry standards – you could see your hand in front of your face – so I pulled on my anorak and hiking boots and sneaked out onto the hills, thankful that I didn’t bump into anyone on the way.

Depending on how you look at it, or how good you are at dealing with it, Dungarry is either the best or the worst place on earth for confronting your demons. It’s on the northern coast of the Isle of Skye, so about as remote as you can get without being really silly and heading for the Outer Hebrides, and apart from the hostel, the Jenny and a couple of houses and farms down the road, there’s absolutely nothing there: it’s all hills, rocks, sheep, sea and silence – booming, thunderous silence. There’s no name for a place like it: you couldn’t even call the few homes and amenities there a village, dwarfed as they are by the hills and so spread out that by the time you’ve walked around it you’ve got to a whole other village without even realising. And that’s not a village either.

In that sense it’s a boon for the imagination: there’s nothing false and very little man-made there to confine it; you have to draw the boundaries, fill in the details, do all the invention yourself. And you might think that even the stoniest of hearts could hardly stand on top of a hill, as I was doing now, in the middle of that terrible, searing beauty, a valley plunging away to my left and a cliff skyscraping to my right and the sea vanishing miles ahead of me, and not feel inspired. But I’d managed it, for the best part of a year. It’s almost funny that it took a daft writing competition, one I hadn’t even entered yet, to make me see that landscape properly for the first time – and, right in the middle of it, the complete prick I’d been for closing my heart and mind to it for so long. Of course, complete prickness went back further than just Dungarry, and as memories of the time before I arrived started to burn into me, there was nothing much I could do except stand there and cry in great racking sobs which shook my whole body, leaving me kneeling with my face in my hands in the soaking grass, the great woolly arses of sheep scattering in every direction.

After about ten minutes of whimpering helplessly in the mud, it got easier. Gradually managing to smile, I walked in the hills all that morning and most of the afternoon, fuelled as much by adrenalin as my extra breakfast. By the time I got back to the hostel, I had a second complete idea for a novel to add to the first, but again I put it out of my mind, too shattered to contemplate it.

I crashed out, woke up a few hours later, went down to the kitchen, knocked up a quick dinner, and still not keen to speak to anyone, decided to eat it in my room. On the way upstairs I passed the office, and just inside the door was a ream of yellow A4 we used for the fax machine, roughly torn open as if in haste, with several sheets of the crisp new paper sticking out temptingly. It was quiet in the hostel and George, my boss, wasn’t about. I tried to ignore it, protesting to myself that my dinner was getting cold, but the yellow paper wasn’t having it. Knowing I’d regret it, but with no idea exactly how much, I took a few sheets and a biro and went up to my room.

I sat down at my desk, tossed down the paper and ate my dinner. Afterwards I looked out the window for a long time, smoking and gazing over the sea, while the yellow paper seethed silently in the corner of the room like a sulking girlfriend. I wasn’t sure what I was more afraid of, writing the ideas down or not writing them down: if I wrote them, the whole thing might start all over again and I’d end up back where I was before, frustrated, messed up and lonely, but if I didn’t write them, the ideas, promiscuous things that they are, would fly off across the universe and into the head of someone who actually wanted them, following which I would forget them, the competition would come and go and I’d spend the next two years scrubbing toilets and kicking myself. In short, I didn’t know what to do... and then I remembered the monk.

*

Fon was Thai, and we were married in her home village just outside Hat Yai, a bustling market town in the south of the country. Her family, who were some of the warmest and most impeccably hospitable people I’ve ever met, had given me a number of gifts, among them a special Buddhist pendant. Inside a triangular glass locket about two inches in length and framed in bright gold was a likeness, carved intricately in dark stone, of Luan Po Tuad, a seventeenth-century monk particularly revered in the south and loved by Fon’s family. Images of the monk – a thin, stooped, wrinkled old man, either sat cross-legged or walking with a stick in one hand and a furled umbrella in the other – were as omnipotent as those of King Bhumibol and other members of the royal family, and could be seen in shops and eating houses, inside taxis, and in people’s homes, especially those of Fon’s parents and siblings. To pay their respects, bring themselves luck and protect themselves from misfortune, Buddhist Thais would bow to likenesses of such monks, pray to them and carry them around with them wherever they went. To be given the pendant by the family, as I was the night before Fon and I flew back to London after our honeymoon, was to be officially accepted into the household, the family, the culture, the country, the region, and the religion all at the same time. As a white suburban Englishman for whom prayer had never meant much more than ‘give us this day our daily bread’, I was honoured and deeply touched. I wore it every day, kissing and bowing to it as I put it on in the morning and took it off at night and again whenever I was in need of help or strength. I wasn’t fanatical about it, not least because a fanatical Buddhist is a contradiction in terms, but I embraced the gift with the respect I felt being given it deserved. It seemed to fill a hole in me I hadn’t known was there until that day.

When Fon left me and I ran away from what had been our home, the locket was one of the few things I took with me, not just because I was unable to look a selfless monk or Fon’s family in the eye, even from a distance, and disown them. I needed guidance and strength of spirit, that was for sure, although under the circumstances I didn’t know whether I had a right to ask for them. I didn’t feel worthy of anything much, least of all the ministrations of a Buddhist monk, and perhaps worst of all I knew that holding on to it would make it impossible for me to truly put everything behind me. In the end I reached a compromise: with one last kiss and bow, as apologetic as it was reverential, I wrapped it up in the tiny green velvet sack it had come in and buried it in a corner of my suitcase, where I resolved to keep it until I felt the time was right to take it out again.

There had been a number of occasions over the year that followed that I’d wanted to open the case, but each time it was the same low self-esteem that stopped me. This evening, things felt different; right, somehow. I blew the dust off the case, opened it and took the locket from the sack, a distortion of my own distorted face rising and falling in its curved glass. Clearing a space on the floor of my room, I knelt down, bowed to an imaginary Buddha three times, and holding the monk’s likeness between my palms as I used to do, prayed silently for a long time. Apologising for my neglect – of the monk, of Fon, of my parents, of many people and many things – and asking for forgiveness and guidance, it was probably more a Christian kind of prayer than a Buddhist one, but my Church of England upbringing, mild as it was, had obviously left its traces. In any case, I’ve never been one for labels.

When I opened my eyes again I found more than an hour had passed. I went to the desk, lit a fag and sat up writing until three o’clock the next morning.