George was a twenty-five-year-old Californian whose father owned the building. With his aviator sunglasses, frayed bell-bottoms and long hair that lankly traced the exact contours of his skull, he could have walked straight off the set of Easy Rider; that said, there was no irony about him, and he was no trendy sixties revivalist; he was just born that way, the real deal. Despite the yawning abyss between the Skye climate and that of his homeland, he and Dungarry seemed made for each other, both of them being ponderous, thoughtful and resistant to change. Nothing was ever too much trouble for him, if for the only reason that his answer to every problem was... nothing. ‘Don’t worry, man,’ he’d say when the roof leaked or the boiler exploded: ‘It’s cool.’ I’d suggest we get hold of Vince – he could fix anything – but George would continue to maintain that everything was ‘cool’ and carry on doing nothing. And then, just when the problem was reaching catastrophic proportions, he’d disappear completely. You’d panic, and when he turned up again, the thing would be fixed. When you asked him what had been going on, he’d say: ‘Don’t worry, man. It’s cool.’

If George ever appreciated the irony of describing everything as ‘cool’ in a place as freezing as Dungarry I never noticed it. But he was a lovely guy, and an ally at a time when I didn’t think I could ever have a friend again. That said, it’s true I still haven’t told him everything that happened to me before we met, but then he’s never asked, and that’s an important part of our friendship. And even if I did tell him, I think I can guess his response.

I didn’t come straight to Dungarry when I left London. I had no idea where to go but I had a bit of cash and didn’t have to work – thankfully, since the state I was in at the time made me more or less unemployable – so for a few weeks I travelled around the country, staying in youth hostels in places like Bristol and York and the Lake District. After a while it seemed everything was drawing me towards Scotland: it was a place I’d never been, where I knew no-one and had no ties. I had no concept of its geography, but an island was what I felt I was at the time, so Skye seemed perfect. I stayed in all the main towns – Armadale, Broadford, Portree – for a few nights each before ending up in Dungarry, where the only option left for all but the most die-hard Skye tourist is to stay or go back on yourself. By then I was spent out in both senses, so I stayed. I’d barely spoken to anyone in the previous month, and wasn’t keen to start, but I was the only guest in the hostel when I first turned up, and George was such a gentle, hospitable guy that when on the third night he offered me a can of Stella, I accepted. He put on a CD of Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here and we started chatting.

I was intrigued to find that George was far from the space-cowboy first impressions his laid-back appearance had suggested. He was well-read, and it turned out we had a shared affection for T.S. Eliot. George could quote whole chunks from, of all things, The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. ‘I love that bit about disturbing the universe,’ he said, turning up his palms. ‘Like, why disturb the universe? It’s much better off left as it is.’

‘Is that what it means?’ I said.

‘I guess so,’ said George. ‘Why, what do you think it means?’

I was going to say I thought that wondering if you dared disturb the universe was the sort of thing you might do if you were full of regrets and felt ineffectual and alienated and old before your time and as if life had passed you by and it was too late to make any difference to anything. And then I was going to mutter darkly about being a pair of ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas, and disappear without a further word to bed. But although that was how I felt, and I may have had good reason, I stayed in my seat and sipped my beer in silence. George was friendly and didn’t deserve to be at the receiving end of some bitter diatribe. ‘I don’t know,’ I said, ‘maybe you’re right. I like that: “why disturb the universe.”’

‘If more people thought like that,’ he said, ‘and less people thought their lives would be meaningless unless they went and interfered with things, the world would be a much happier place.’

I winced, the words nauseating me as much for how they reminded me of the mistakes I’d made with Fon as for their naive simplicity. But I still didn’t say anything, and we opened another beer and moved on to Ernest Hemingway.

Under other circumstances I might have mistaken George’s non-interventionist approach to life for vacuous, airheaded optimism, but at that time I didn’t care what it was; he was a breath of fresh air, and I was grateful for his lack of inquisitiveness. In fact, almost the only other question he ever asked me was about two weeks later. ‘You like it here, don’t you?’ he said.

‘Very much,’ I said.

He didn’t say anything, and then I found myself adding, ‘I thought I might go down to Portree and see if I can get a job somewhere.’ I hadn’t thought that at all before that moment, although it was true I’d run out of money and didn’t have any particular desire to leave Skye.

‘Why don’t you stay here?’ he said. ‘I could do with some help.’

‘Really?’

‘Sure... I’ve got fifty-two beds here. It doesn’t pay very well, and you’d have to clean the john, that sorta stuff. But you get your own room and all you can eat. How about it?’

It was as simple as that. There was no employment contract, and George paid me in cash, but for once in my life I didn’t care. It quickly became clear that George wasn’t going anywhere and I would have the job for as long as I wanted it. A mutual trust had somehow been established, and that was all that mattered. It still seems funny to me, because you couldn’t wish to meet two more different people than George and me. But then, why disturb the universe?

*

Up to now I’d been scribbling my ideas on the yellow paper nicked from the office, but as my big ideas became bigger, my pockets started to bulge, my room began to disappear and I started losing important things I’d written. I no longer owned a proper notebook; I’d left all my writing gear, from paper to laptop, in my flat. It was clear I needed a new one, and since there were no shops in Dungarry, a trip to Portree, Skye’s miniature ‘capital’, was in order.

Portree was an hour’s drive away, and while not necessarily the closest source of notebooks and other items less than essential for survival, it was the most picturesque. A map would show you that, like Dungarry, Portree was on the sea’s edge, but while Dungarry’s rocks were constantly foam-dashed in time-honoured British tradition, when you walked around Portree’s haunting cliff path your eyes told you what you were looking at was an enormous black lake which wouldn’t have been out of place further south in Cumbria. By contrast, the harbour was much more gentle, with Mediterranean-style fishing boats and, around the bay, a crescent of front doors each painted a different colour. Tourism accounted for most of the town’s business, so those front doors opened almost exclusively into guesthouses, and a good half of the shops sold little else but tartan-hued and whisky-flavoured variations on just about any gift you could think of. More originally, a newish shop called Skye Batiks did a roaring trade in dazzling hand-made clothes printed with beautiful Celtic designs and Escher-like interlocking birds and fish. There was also a bakery-cum-café in the town centre whose speciality was a steak sandwich, or ‘steakwich’ as they called it, to which I was rather partial.

I was thinking about all this as I was waiting for the minibus up the road from the hostel. With ten minutes to spare, I lit a cigarette and blew blue smoke into the damp air. I knew the bus times by heart, and you could set your watch by them, but they only came once every two hours and I could never trust myself not to miss one, so I was always there early. The bus stop itself was actually a gate opening off the main road onto a path down to the Jenny. I was daydreaming about a solitary stroll around the cliff path and a long gaze into what I still considered the town’s black lake when car tyres crunched juicily up the wet, stony ground behind me.

‘Stevie-boy!’ said Vince, leaning out of his black Jag. ‘What’re you up to?’

‘Alright, Vince. Just going into Portree.’

‘What, on the bus?’ He made it sound as if I’d said I was going to Mars by donkey.

‘No,’ I said, ‘I thought if I waited here long enough the ground would freeze over and I could skate there.’

‘Stevie-boy,’ he grinned. ‘I’m going there myself. Hop in.’

I couldn’t exactly refuse. I’d barely got my seatbelt on when he started.

‘What’re you doing in Portree?’ he said. He was driving with his right hand, or rather his whole arm, on the steering wheel, while rolling a cigarette with his left.

‘I’m not there yet, am I,’ I said.

‘What’re you going there for, then?’

‘Just some stuff.’

‘Stuff?’

‘Yeah, some shopping, a few bits and pieces.’

‘Ah, you should’ve asked me, I’d’ve got it for you.’

‘Well, you know – I haven’t been there for a while. Fancied a stroll.’

‘A stroll? Around Portree? You can do it in five minutes, can’t you?’

‘I don’t mean the town, I mean the lake. You know, the sea. The harbour, the cliff path, all that.’

‘Oh, aye. What’re you gonna buy?’

‘Like I said, just some stuff.’

‘Come on!’

I couldn’t believe I was in for another fifty minutes of this.

‘First, you tell me why you’re going to Portree,’ I said.

‘Oh, nothin’ much. See my girlfriend, you know.’

‘Your girlfriend...’ I said, trying to cover up the fact that I had no idea who he was going out with at that moment.

‘Margaret,’ he said, smiling. ‘Ah, what a beautiful word, eh? “Margaret.”’

‘Oh, Margaret,’ I said. ‘Isn’t she the one sort of with – brown hair and – ’

‘You haven’t met her yet,’ he said. ‘Well, I mean you might’ve done, but...’

‘I probably have,’ I said, ‘if she’s from Skye.’

‘Oh, she’s from Skye all right... Skye born and bred. Speaks the Gaelic and everything.’ The Scots dialect was pronounced ‘garlic’.

I chuckled. ‘I still can’t get used to that expression. It always makes me think it’s some secret language spoken only by chefs.’

‘Anyway,’ said Vince, ‘you still haven’t told me what you’re going to buy in Portree.’

I sighed. ‘A notebook.’

‘A what?’

‘A notebook. A book for making notes in.’

‘Oh, aye! What d’you want one of them for?’

‘For making notes, Vince.’

‘About what?’

‘About – ideas I’ve had.’

‘Ideas!’ he said. ‘You want to be careful with them, you know. Ideas can be dangerous things.’

I laughed. ‘I shouldn’t think my ideas would do much harm.’ Then I thought of the ideas I’d had which had driven my wife away, and stopped smiling.

‘Whenever I get any ideas,’ he said, ‘I tell ’em to piss off. Not that I really have any ideas, that is, but if I did...’

‘Why do you do that?’ I said. ‘You might have a good idea one day. You tell it to go away and then you spend the rest of your life wishing it’d come back.’

‘Naw,’ he said. ‘All ideas are dangerous. Best ignore ’em. What sort of ideas have you had?’

‘How can you say that?’ I said.

‘What?’

‘You say ideas should be ignored, and in the next breath you want me to tell you about them. You can’t have both, can you?’

He thought for a bit. ‘Well, these are your ideas,’ he said. ‘They don’t count.’

‘Thanks, Vince.’

‘No, I don’t mean they don’t count, I mean – ’

‘I know what you mean. I dunno... they’re nothing very interesting. Not even worth talking about, really. It’s just... stuff.’

‘Stuff?’ he said. ‘You’ve had ideas about stuff? That sounds really dangerous.’

‘What can I say?’ I said, exasperated. ‘My head’s full of stuff at the moment. It just keeps coming.’

‘Sounds like you need to have your sinuses drained,’ said Vince, ‘not a notebook.’

To my relief, Vince’s mobile phone rang then and he spent the next twenty minutes ignoring me entirely while he talked to a woman who wasn’t, frankly, called Margaret.

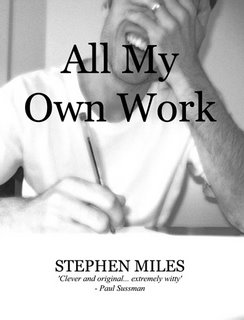

Eventually we got to Portree, where I managed to convince Vince I’d be able to do my shopping and get back by myself. I went into the newsagents-cum-stationers and bought a couple of spiral-bound yellow-paper notebooks, the custard-coloured A4 from the office having seemed lucky. One was pocket-sized for jotting things down whenever they came to me, and the other was a bumper A4 job for spreading my thoughts out in my spare time. I was going to get a few of them, given the amount of writing it looked like I was going to be doing, but I didn’t want to tempt providence. Too much blank paper can be bad luck for a writer; you should only have just enough to be getting along with.

I did have a steakwich at the café, and after that I walked up the cliff path and gazed over the ‘lake’. But the water looked blacker than I remembered it, and the immensity of it scared me. Strange thoughts clouded my mind: the surface of the water was as mirror-smooth as ever, but I couldn’t help thinking that at any moment it would start to rock and dip and something would rise out of it – some huge, black Krakenesque creature the entire length of the lake that had been sleeping deeply in it for centuries. I couldn’t understand it but I didn’t like the idea so I walked back to the bus stop and went home.