From the moment I first read about the Leonard Sankey New Talent In Fiction competition, I knew I had to take a chance and enter it. There was no middle ground: it was either my ticket out of scrubbing shower cubicles in the Rainfall Capital of the British Isles (unofficial) and, hopefully, back into the arms of my estranged wife, or the latest in a long line of professional, financial, emotional, spiritual and literary cul-de-sacs I’d just spent a year or more extricating myself from. Because, hard as it may seem to believe at this end of things, up to that point my writing career had at best been inauspicious, and at worst brought me some serious bad luck, and I was doing all I could to put it behind me once and for all.

I suppose I am something of a veteran of writing competitions, but don’t let that fool you. While I have written a few stories for my own pleasure – pieces that were never intended to fit into (or be mutilated to fit into) the restrictions of whatever new ridiculous rules judging panels could devise – and I have attempted several times to write a novel, one way or another most of my writing has been in the form of submissions to contests. Romances, thrillers, whodunits, horror, historical fiction, travelogues, erotica... whatever the genre, subject, style or theme, you name it, there’s been a competition for it, and I’ve entered it. And, I should add, not won it.

Until now, that is. And now I’m wishing I hadn’t.

The reports you may have read in the papers that I used to have a life of some sort before all this happened are mostly true, but when I first heard about Leonard Sankey and his competition, the flat in London, my wife, my job, a decent income, regular holidays and all the rest of it were already long gone. I’d been working at the Dungarry Inn, a fifty-bed independent youth hostel on the northern tip of the Isle of Skye, for the best part of a year. Things were going as well as could be expected: with the odd exception, I’d managed to stop remembering everything I’d gone there to forget, and was secretly anxious to move on at the next opportunity. My wages were minuscule (most of my work was rewarded with free board and lodging) but I’d been putting money aside for some time, and now had almost enough for a ticket back to the mainland and a month’s deposit on a flat. Despite – or perhaps because of – the friends I had there, putting roots down too deep made me nervous, and if it hadn’t been for what happened I would almost certainly have been back somewhere in England doing a proper job, or at least enrolled on some sort of training course, within a few months. Either way, I certainly didn’t see myself ever going back to writing.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon, the best time of the day. If the hostel ever did come close to serenity, it was then: the guests were either out enjoying Skye’s rugged attractions or making a bowl of noodles in the kitchen or sitting around reading; all the important jobs – the laundry, the sweeping-up, the showers – had been done; everything was clean and tidy and in its place. Even by Dungarry standards, it was quiet: the carpet, a shocking paisley acid trip of reds and oranges, was probably the loudest thing for miles. Dungarry was the quietest, most remote place I’ve ever known – too much so for me sometimes, being a Londoner, but by and large it was still a welcome change from city and suburban life. Of course, the other reason three o’clock was a good time was that I generally knocked off around then, either for the day if I was doing the early shift (which I generally was), or for lunch. Today was an early shift day.

I went to my room on the top floor, pulled on a jumper, and dodged raindrops to the Jenny MacDonald, which wasn’t so much the local pub as the only pub for miles. The Jenny consisted of a single, small room painted entirely in black with a corner bar, a pool table in the centre and seating for about a dozen people. I don’t know whose idea the décor was; when you first visited there was a tendency to think you’d stumbled into a bondage club, but despite its sinister appearance it was actually quite civilised. Apart from me, there were three other hardcore Jenny regulars: Eric, who ran it, Vince, a sort of handyman-at-large, and Alastair, a young unemployed guy who lived nearby. When I turned up they were already there, and as usual, we were the only punters.

‘Shite!’ said Vince as I came in. ‘It’s that London geezer again. Subtitles out for the lad.’

‘Come again?’ I said.

‘Stevie-boy,’ said Eric. ‘What’re you having?’

As usual I sat in my usual place and ordered a pint of my usual bitter, and as usual Eric waved away my money. ‘You should know by now, the first one’s on me,’ he said.

‘I don’t like to presume,’ I said.

‘Ah, presume away. Every other bugger does.’

I lit a Marlboro and opened The Guardian and, with one ear on the conversation, proceeded to half-read it by the slate-grey light slanting in through the window. The weather on Skye could be depressing, but you got used to it after the first six months. In any case, as an old joke went, it was always warm inside Jenny MacDonald’s, especially with your drinks and your cigarettes and your friends.

I should introduce them before I go any further. Eric, a portly Edinburgh native with a sturdiness like the Skye monoliths, was nearly fifty but looked years younger for two reasons. The first was that, after decades of not-altogether-happy bachelordom, he’d recently made up for lost time by getting married and having a baby (it was only just on its way at that point, to be precise), giving him an invincible glow of fatherly pride. It was a whirlwind sort of thing; having never been married or had a family before, he’d met his wife, proposed, tied the knot and conceived the ‘bairn’ all within the previous few months. The second reason for his youthful appearance was that he’d had a face-lift. That wasn’t really what it was – vain was the last word you’d use to describe Eric – but his scalp had been split down the middle after he was bottled by a couple of drunks in a Glasgow car park a few years before, and the resulting surgery had literally lifted his chops, ironing out all the wrinkles in the process. ‘Guess I’m just lucky,’ he’d say when he told you the story.

Vince seemed to be everything Eric wasn’t. Apart from being Glaswegian, he was in his late thirties – a few years older than me – sinewy, fit (despite his prodigious intake of rolling tobacco), and with his blond ponytail and neat beard was a good-looking bastard to boot. He also talked a lot – like, the whole bloody time. If he wasn’t talking to you directly, or nobody in particular, which of course meant you anyway, he’d be talking – invariably to a woman – on his mobile phone; in fact, when his phone rang it was sometimes the only way you could get away from him. I liked Vince, but for different reasons to Eric: it was admiration really, even before I found out what I found out about him later – and despite it.

Alastair was that rare thing on Skye, at least above a certain age: he was from Skye. Most people of his generation who came from the island seemed to want to leave for the mainland and the big cities, but Alastair wasn’t quite ready for that yet. He was similar to Eric in that he also looked younger than he was, but because he was twenty-three and looked twelve, this didn’t work for him in quite the same way. Alastair was like the Highland weather – pouring with rain most of the time with occasional bursts of unaccountably brilliant sunshine. He wore a black bomber jacket all the time, summer or winter, both indoors and out, and regardless of the time of day or the occasion, he never strayed from his tipple of choice – black coffee. He’d come in, Eric would do him his coffee, he’d unzip his jacket, put his tiny silver mobile phone on the table in front of him, and while we chatted, he’d hunch over both the phone – which never, ever rang – and the cup, and slowly dissolve lumps of sugar in it, holding the lump on a spoon on the surface of the drink and watching it dissolve, grain by grain. And when it was all gone, he’d take a new cube and start all over again.

Despite all this, you’d often catch Al out of the corner of your eye trying not to laugh at something one of us had said in case he broke the spell of Serious Young Manliness. Needless to say, Vince would wind him up all the time – not in a nasty way, but to try to get him to chill out. Sometimes it seemed Alastair had grown accustomed to this, but almost every time it happened, Vince – with, it has to be said, a little help from Eric and me – managed to catch him out. Today was no exception.

‘I knew a bloke who had two left feet once,’ said Vince, apropos, as ever, of nothing.

‘You mean he couldn’t dance?’ said Eric.

‘No,’ said Vince matter-of-factly, fingering his pouch of tobacco. ‘I mean he really had two left feet. He was born with his right foot, right, instead of having a big toe on the left going down to the little toe on the right, he had the toes in the same order as his left foot, and it faced, like, out, rather than in. Fascinating.’

‘So he literally couldn’t dance?’ I said.

‘Don’t mock the afflicted,’ said Eric.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘George W. Bush excepted.’

‘Actually,’ said Vince, ‘he could dance – this was the thing.’

‘Who, George W. Bush?’

‘No,’ moaned Vince, ‘this guy I’m talking about.’

‘Really? With the two left feet?’

‘Yup.’

‘No way!’

‘Aye. He’d had the piss taken out of him all his life – “Two left feet! You can’t dance!” All that. So he made a huge effort to learn, and he worked so hard at it that he became really fucking good.’

‘That’s a nice story,’ I said.

‘What was his name?’ said Alastair, pretending not to be utterly captivated.

‘Fred,’ said Vince.

‘Fred what?’

‘Astaire.’

Vince lit the cigarette he’d been rolling, Eric took a sip of his drink and I turned a page of my paper. Alastair sat there with his mouth open. ‘No way!’ he said.

‘Straight up.’

‘But – ’

‘It’s true,’ said Vince. ‘Every word I say is true. You should know that by now...’

It was then I saw the story. The conversation faded into the background as I read it. I still have the cutting:

Sankey Prize ‘disinherited’ in favour of new talent

by Julie Miller, Arts Correspondent

Leonard Sankey, who died last month at the age of 86, has ‘disinherited’ the prize that bears his name.

The eccentric millionaire novelist and philanthropist left instructions in his will that the Sankey Prize for Fiction – Britain’s most sought-after literary accolade after the Booker Prize – should be revamped to help establish previously unpublished authors. The Sankey prize, like the Booker, was formerly open only to novels that were already published.

Close friends were unsurprised by the announcement, saying that since his diagnosis with cancer, Sankey had become ‘remorseful’ for ‘shoring up the literary mafia’ at the expense of struggling new talent.

Sankey established his original prize in 1985 after his novels The Barber of Southfields and The Stepney Wives had been shortlisted for the Booker but failed to win. These unpopular decisions were ascribed variously to literary snobbery and publishing politics, although Sankey, whose novels enjoyed critical acclaim as well as huge commercial success, notoriously preferred the term ‘Booker bollocks’.

The new competition, to be called the Sankey Awards for New Talent in Fiction, is almost unprecedented in the UK. Instead of awarding £20,000 each year to one established author, five formerly unpublished writers selected every two years will each be awarded £10,000 and a place on a creative writing course to help them complete and publish their first novel. Entries will initially be judged on the strength of the first two chapters of the novel and an outline of the whole work. The new competition is expected to open in the next few weeks.

Former Sankey prize winner Rebecca Burgess said, ‘The new prize is a fantastic idea; it’s a real boon to new talent. Leonard was a wonderful man; even in death he is reinventing himself.’

Literary agent Martin Daniels also welcomed the encouragement of new writers but said it was sad to see the passing of the only literary award to ‘seriously rival’ the Booker. ‘And I don’t envy the judges either,’ he said. ‘They’re going to be swamped.’

‘What do you think, Stevie-boy?’ said Vince.

‘Sorry, what?’

‘We’ve lost him, guys.’

‘Earth calling Stephen Miles...’

‘No, I was just reading... what were you saying?’

I carried on chatting but my mind was elsewhere. As soon as I’d read the article through I turned the page and tried to cast it out of my mind. I was already getting butterflies just thinking about the competition: the challenge of it, the range of possibilities, the story, the characters, the accomplishment, the satisfaction, the money, the fame, the freedom, the women... or rather the woman.

What you’re reading now is a true story. As such, it’s a memoir, although at times it will read like fiction.

You couldn't make it up

Background...

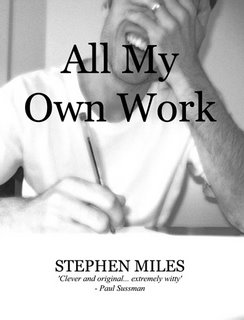

- Steve Miles

- A few years ago my novel "All My Own Work" was named a winner of The Leonard Sankey Awards for New Talent in Fiction (www.sankeyawards.org.uk). Billed at the time as one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the UK, it promised a cheque for £10,000, a place on a top-quality writing course and the guidance of a professional editor. However, as well reported in the media at the time, I was controversially stripped of the award and "All My Own Work" was never published - until now...