From the moment I first read about the Leonard Sankey New Talent In Fiction competition, I knew I had to take a chance and enter it. There was no middle ground: it was either my ticket out of scrubbing shower cubicles in the Rainfall Capital of the British Isles (unofficial) and, hopefully, back into the arms of my estranged wife, or the latest in a long line of professional, financial, emotional, spiritual and literary cul-de-sacs I’d just spent a year or more extricating myself from. Because, hard as it may seem to believe at this end of things, up to that point my writing career had at best been inauspicious, and at worst brought me some serious bad luck, and I was doing all I could to put it behind me once and for all.

I suppose I am something of a veteran of writing competitions, but don’t let that fool you. While I have written a few stories for my own pleasure – pieces that were never intended to fit into (or be mutilated to fit into) the restrictions of whatever new ridiculous rules judging panels could devise – and I have attempted several times to write a novel, one way or another most of my writing has been in the form of submissions to contests. Romances, thrillers, whodunits, horror, historical fiction, travelogues, erotica... whatever the genre, subject, style or theme, you name it, there’s been a competition for it, and I’ve entered it. And, I should add, not won it.

Until now, that is. And now I’m wishing I hadn’t.

The reports you may have read in the papers that I used to have a life of some sort before all this happened are mostly true, but when I first heard about Leonard Sankey and his competition, the flat in London, my wife, my job, a decent income, regular holidays and all the rest of it were already long gone. I’d been working at the Dungarry Inn, a fifty-bed independent youth hostel on the northern tip of the Isle of Skye, for the best part of a year. Things were going as well as could be expected: with the odd exception, I’d managed to stop remembering everything I’d gone there to forget, and was secretly anxious to move on at the next opportunity. My wages were minuscule (most of my work was rewarded with free board and lodging) but I’d been putting money aside for some time, and now had almost enough for a ticket back to the mainland and a month’s deposit on a flat. Despite – or perhaps because of – the friends I had there, putting roots down too deep made me nervous, and if it hadn’t been for what happened I would almost certainly have been back somewhere in England doing a proper job, or at least enrolled on some sort of training course, within a few months. Either way, I certainly didn’t see myself ever going back to writing.

It was three o’clock in the afternoon, the best time of the day. If the hostel ever did come close to serenity, it was then: the guests were either out enjoying Skye’s rugged attractions or making a bowl of noodles in the kitchen or sitting around reading; all the important jobs – the laundry, the sweeping-up, the showers – had been done; everything was clean and tidy and in its place. Even by Dungarry standards, it was quiet: the carpet, a shocking paisley acid trip of reds and oranges, was probably the loudest thing for miles. Dungarry was the quietest, most remote place I’ve ever known – too much so for me sometimes, being a Londoner, but by and large it was still a welcome change from city and suburban life. Of course, the other reason three o’clock was a good time was that I generally knocked off around then, either for the day if I was doing the early shift (which I generally was), or for lunch. Today was an early shift day.

I went to my room on the top floor, pulled on a jumper, and dodged raindrops to the Jenny MacDonald, which wasn’t so much the local pub as the only pub for miles. The Jenny consisted of a single, small room painted entirely in black with a corner bar, a pool table in the centre and seating for about a dozen people. I don’t know whose idea the décor was; when you first visited there was a tendency to think you’d stumbled into a bondage club, but despite its sinister appearance it was actually quite civilised. Apart from me, there were three other hardcore Jenny regulars: Eric, who ran it, Vince, a sort of handyman-at-large, and Alastair, a young unemployed guy who lived nearby. When I turned up they were already there, and as usual, we were the only punters.

‘Shite!’ said Vince as I came in. ‘It’s that London geezer again. Subtitles out for the lad.’

‘Come again?’ I said.

‘Stevie-boy,’ said Eric. ‘What’re you having?’

As usual I sat in my usual place and ordered a pint of my usual bitter, and as usual Eric waved away my money. ‘You should know by now, the first one’s on me,’ he said.

‘I don’t like to presume,’ I said.

‘Ah, presume away. Every other bugger does.’

I lit a Marlboro and opened The Guardian and, with one ear on the conversation, proceeded to half-read it by the slate-grey light slanting in through the window. The weather on Skye could be depressing, but you got used to it after the first six months. In any case, as an old joke went, it was always warm inside Jenny MacDonald’s, especially with your drinks and your cigarettes and your friends.

I should introduce them before I go any further. Eric, a portly Edinburgh native with a sturdiness like the Skye monoliths, was nearly fifty but looked years younger for two reasons. The first was that, after decades of not-altogether-happy bachelordom, he’d recently made up for lost time by getting married and having a baby (it was only just on its way at that point, to be precise), giving him an invincible glow of fatherly pride. It was a whirlwind sort of thing; having never been married or had a family before, he’d met his wife, proposed, tied the knot and conceived the ‘bairn’ all within the previous few months. The second reason for his youthful appearance was that he’d had a face-lift. That wasn’t really what it was – vain was the last word you’d use to describe Eric – but his scalp had been split down the middle after he was bottled by a couple of drunks in a Glasgow car park a few years before, and the resulting surgery had literally lifted his chops, ironing out all the wrinkles in the process. ‘Guess I’m just lucky,’ he’d say when he told you the story.

Vince seemed to be everything Eric wasn’t. Apart from being Glaswegian, he was in his late thirties – a few years older than me – sinewy, fit (despite his prodigious intake of rolling tobacco), and with his blond ponytail and neat beard was a good-looking bastard to boot. He also talked a lot – like, the whole bloody time. If he wasn’t talking to you directly, or nobody in particular, which of course meant you anyway, he’d be talking – invariably to a woman – on his mobile phone; in fact, when his phone rang it was sometimes the only way you could get away from him. I liked Vince, but for different reasons to Eric: it was admiration really, even before I found out what I found out about him later – and despite it.

Alastair was that rare thing on Skye, at least above a certain age: he was from Skye. Most people of his generation who came from the island seemed to want to leave for the mainland and the big cities, but Alastair wasn’t quite ready for that yet. He was similar to Eric in that he also looked younger than he was, but because he was twenty-three and looked twelve, this didn’t work for him in quite the same way. Alastair was like the Highland weather – pouring with rain most of the time with occasional bursts of unaccountably brilliant sunshine. He wore a black bomber jacket all the time, summer or winter, both indoors and out, and regardless of the time of day or the occasion, he never strayed from his tipple of choice – black coffee. He’d come in, Eric would do him his coffee, he’d unzip his jacket, put his tiny silver mobile phone on the table in front of him, and while we chatted, he’d hunch over both the phone – which never, ever rang – and the cup, and slowly dissolve lumps of sugar in it, holding the lump on a spoon on the surface of the drink and watching it dissolve, grain by grain. And when it was all gone, he’d take a new cube and start all over again.

Despite all this, you’d often catch Al out of the corner of your eye trying not to laugh at something one of us had said in case he broke the spell of Serious Young Manliness. Needless to say, Vince would wind him up all the time – not in a nasty way, but to try to get him to chill out. Sometimes it seemed Alastair had grown accustomed to this, but almost every time it happened, Vince – with, it has to be said, a little help from Eric and me – managed to catch him out. Today was no exception.

‘I knew a bloke who had two left feet once,’ said Vince, apropos, as ever, of nothing.

‘You mean he couldn’t dance?’ said Eric.

‘No,’ said Vince matter-of-factly, fingering his pouch of tobacco. ‘I mean he really had two left feet. He was born with his right foot, right, instead of having a big toe on the left going down to the little toe on the right, he had the toes in the same order as his left foot, and it faced, like, out, rather than in. Fascinating.’

‘So he literally couldn’t dance?’ I said.

‘Don’t mock the afflicted,’ said Eric.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘George W. Bush excepted.’

‘Actually,’ said Vince, ‘he could dance – this was the thing.’

‘Who, George W. Bush?’

‘No,’ moaned Vince, ‘this guy I’m talking about.’

‘Really? With the two left feet?’

‘Yup.’

‘No way!’

‘Aye. He’d had the piss taken out of him all his life – “Two left feet! You can’t dance!” All that. So he made a huge effort to learn, and he worked so hard at it that he became really fucking good.’

‘That’s a nice story,’ I said.

‘What was his name?’ said Alastair, pretending not to be utterly captivated.

‘Fred,’ said Vince.

‘Fred what?’

‘Astaire.’

Vince lit the cigarette he’d been rolling, Eric took a sip of his drink and I turned a page of my paper. Alastair sat there with his mouth open. ‘No way!’ he said.

‘Straight up.’

‘But – ’

‘It’s true,’ said Vince. ‘Every word I say is true. You should know that by now...’

It was then I saw the story. The conversation faded into the background as I read it. I still have the cutting:

Sankey Prize ‘disinherited’ in favour of new talent

by Julie Miller, Arts Correspondent

Leonard Sankey, who died last month at the age of 86, has ‘disinherited’ the prize that bears his name.

The eccentric millionaire novelist and philanthropist left instructions in his will that the Sankey Prize for Fiction – Britain’s most sought-after literary accolade after the Booker Prize – should be revamped to help establish previously unpublished authors. The Sankey prize, like the Booker, was formerly open only to novels that were already published.

Close friends were unsurprised by the announcement, saying that since his diagnosis with cancer, Sankey had become ‘remorseful’ for ‘shoring up the literary mafia’ at the expense of struggling new talent.

Sankey established his original prize in 1985 after his novels The Barber of Southfields and The Stepney Wives had been shortlisted for the Booker but failed to win. These unpopular decisions were ascribed variously to literary snobbery and publishing politics, although Sankey, whose novels enjoyed critical acclaim as well as huge commercial success, notoriously preferred the term ‘Booker bollocks’.

The new competition, to be called the Sankey Awards for New Talent in Fiction, is almost unprecedented in the UK. Instead of awarding £20,000 each year to one established author, five formerly unpublished writers selected every two years will each be awarded £10,000 and a place on a creative writing course to help them complete and publish their first novel. Entries will initially be judged on the strength of the first two chapters of the novel and an outline of the whole work. The new competition is expected to open in the next few weeks.

Former Sankey prize winner Rebecca Burgess said, ‘The new prize is a fantastic idea; it’s a real boon to new talent. Leonard was a wonderful man; even in death he is reinventing himself.’

Literary agent Martin Daniels also welcomed the encouragement of new writers but said it was sad to see the passing of the only literary award to ‘seriously rival’ the Booker. ‘And I don’t envy the judges either,’ he said. ‘They’re going to be swamped.’

‘What do you think, Stevie-boy?’ said Vince.

‘Sorry, what?’

‘We’ve lost him, guys.’

‘Earth calling Stephen Miles...’

‘No, I was just reading... what were you saying?’

I carried on chatting but my mind was elsewhere. As soon as I’d read the article through I turned the page and tried to cast it out of my mind. I was already getting butterflies just thinking about the competition: the challenge of it, the range of possibilities, the story, the characters, the accomplishment, the satisfaction, the money, the fame, the freedom, the women... or rather the woman.

What you’re reading now is a true story. As such, it’s a memoir, although at times it will read like fiction.

Friday, June 24, 2005

Friday, June 17, 2005

Prologue

It’s gone eleven one Saturday night. I’m sitting at the laptop by the lounge window, writing, drinking wine, waiting for Fon to come home from the restaurant. We haven’t been going out that long, but long enough for her to stay the night once or twice a week. I’ve got Abbey Road on the stereo, the old vinyl LP I’ve had since I was about ten crackling warmly in the evening room. It’s one of the first records I ever bought, and although by now my collection is several hundred strong, this is one of probably only a dozen albums I play on a regular basis. As her key scrapes in the door, the needle’s about half way through the last track on side one – I Want You (She’s So Heavy).

“Hi!”

“Hallo tee-rak,” she says, using the Thai word for ‘darling’, and kisses me.

“Good evening?”

“Yes, very good. Very busy. Loss of tips!”

“Why, what happened? Where’d you lose them?”

“Lose?”

“You just said ‘loss of tips’?”

“No,” she says, digging in her pocket to rustle notes and jingle coins at me. “Lots of tips!”

“Oh, right. Well done.”

“What’s this music?”

“It’s The Beatles, darling.”

“The Beatles?” She looks at me, her lip curled Elvis-style, as if I just told her it was the Queen Mother. “The Beatles don’t make records like this.”

“Didn’t make records,” I correct.

“Didn’t make records,” she repeats.

“Anyway, they certainly did... why, have you never heard this before?”

“Never,” she says.

“You’re kidding!” I’m not being sarcastic or snobbish – it really is the first time I’ve ever met anyone who hasn’t heard the record. Suddenly far more than just my umpteenth listen of an old classic, it’s an occasion to rise to. “Well, you’re in for a treat,” I say. “This is Abbey Road. Their last album. And one of the best albums ever made by anyone in the entire history of the universe.”

“Really?” she says as if it’s gospel, putting her bag down and fishing out a packet of Consulates. Lighting up, she ponders John Lennon wrenching out another primal scream of desire over the swelling guitars, organ and drums. “It’s very strange,” she announces, and sits down opposite me, unfurling a Thai magazine with a photo of a smart, regal-looking woman on the cover. It’s either their queen or the princess – I always confuse the two.

“Not all the tracks are like this,” I say, just to be sure.

“Mmm,” she says, inhaling the fragrant smoke, well into the magazine.

I decide not to say anything more about the record, mostly because I’m listening to it and she’s reading but also because I want to see what happens in a minute.

“She’s so – ”

The band breaks into that intoxicating coda: swirling and building, intense and huge, it slowly threatens to fill the room and our heads with an endless orgasm of white noise. She glances up at the stereo and then at me, pulling a face which says Are you absolutely sure about this?, directed as much at the group for making the record as me for loving it so much. I smile back at her, resisting the temptation to turn the stereo down. She returns to the magazine but I keep my eye on her face over the lost horizon of the laptop screen.

In more than two decades of listening to the album, I’ve never once counted the number of times the band repeats the final figure, and despite being a big Beatles fan I’m not enough of an anorak to want to know. However, even though the last repetition starts out no differently from any of the others, the song has been absorbed into my unconscious to such an extent that I can always tell when the track’s about to end. This time is no exception: as the final arpeggio gradually works its way to the climax, I study Fon’s face, hardly daring to blink in case I miss the moment. She’s still reading, the endless music now just wallpaper to her ears, her eyes firmly down on the page of Thai. And then,

shikk

Suddenly there’s nothing – it’s as if all the air has been sucked out of the room and we’re sitting in a vacuum. The track, the album, the whole evening all come to a halt, leaving us in the middle of nowhere. Fon’s face flashes up at me like someone bursting back to consciousness from a dream, her mouth open, her eyes the definition of surprise. It’s history in the making... I wish I had a camera.

“What!” she says, and I laugh.

Actually, I’m glad I haven’t got that camera: you take a photo and you forget the image, or you forget the moment you took it. It’d only end up as one of the million silly snaps all couples take of each other. I realise I’m lucky to have that image of her face as it was when she first heard the abrupt ending of I Want You (She’s So Heavy), along with every other detail, every rustle and crackle of that record, imprinted forever on my memory.

Or at least I was – lucky, I mean. I was never able to listen to that track again without remembering that evening, the happiness and cosiness of it, and Fon’s face. That was good for a long time but then I couldn’t listen to it without remembering the innocence we still had of each other and of the difficulties and heartbreaks that were yet to come.

The last time I listened to Abbey Road must have been a few weeks before I moved out of the flat, which itself was a few months after Fon left. If our relationship just before that time sounded like the swirling, maddening coda of I Want You (She’s So Heavy), her leaving sounded like the sudden silence as the track ended and the needle lifted off the spinning vinyl. I don’t even have the album anymore.

“Hi!”

“Hallo tee-rak,” she says, using the Thai word for ‘darling’, and kisses me.

“Good evening?”

“Yes, very good. Very busy. Loss of tips!”

“Why, what happened? Where’d you lose them?”

“Lose?”

“You just said ‘loss of tips’?”

“No,” she says, digging in her pocket to rustle notes and jingle coins at me. “Lots of tips!”

“Oh, right. Well done.”

“What’s this music?”

“It’s The Beatles, darling.”

“The Beatles?” She looks at me, her lip curled Elvis-style, as if I just told her it was the Queen Mother. “The Beatles don’t make records like this.”

“Didn’t make records,” I correct.

“Didn’t make records,” she repeats.

“Anyway, they certainly did... why, have you never heard this before?”

“Never,” she says.

“You’re kidding!” I’m not being sarcastic or snobbish – it really is the first time I’ve ever met anyone who hasn’t heard the record. Suddenly far more than just my umpteenth listen of an old classic, it’s an occasion to rise to. “Well, you’re in for a treat,” I say. “This is Abbey Road. Their last album. And one of the best albums ever made by anyone in the entire history of the universe.”

“Really?” she says as if it’s gospel, putting her bag down and fishing out a packet of Consulates. Lighting up, she ponders John Lennon wrenching out another primal scream of desire over the swelling guitars, organ and drums. “It’s very strange,” she announces, and sits down opposite me, unfurling a Thai magazine with a photo of a smart, regal-looking woman on the cover. It’s either their queen or the princess – I always confuse the two.

“Not all the tracks are like this,” I say, just to be sure.

“Mmm,” she says, inhaling the fragrant smoke, well into the magazine.

I decide not to say anything more about the record, mostly because I’m listening to it and she’s reading but also because I want to see what happens in a minute.

“She’s so – ”

The band breaks into that intoxicating coda: swirling and building, intense and huge, it slowly threatens to fill the room and our heads with an endless orgasm of white noise. She glances up at the stereo and then at me, pulling a face which says Are you absolutely sure about this?, directed as much at the group for making the record as me for loving it so much. I smile back at her, resisting the temptation to turn the stereo down. She returns to the magazine but I keep my eye on her face over the lost horizon of the laptop screen.

In more than two decades of listening to the album, I’ve never once counted the number of times the band repeats the final figure, and despite being a big Beatles fan I’m not enough of an anorak to want to know. However, even though the last repetition starts out no differently from any of the others, the song has been absorbed into my unconscious to such an extent that I can always tell when the track’s about to end. This time is no exception: as the final arpeggio gradually works its way to the climax, I study Fon’s face, hardly daring to blink in case I miss the moment. She’s still reading, the endless music now just wallpaper to her ears, her eyes firmly down on the page of Thai. And then,

shikk

Suddenly there’s nothing – it’s as if all the air has been sucked out of the room and we’re sitting in a vacuum. The track, the album, the whole evening all come to a halt, leaving us in the middle of nowhere. Fon’s face flashes up at me like someone bursting back to consciousness from a dream, her mouth open, her eyes the definition of surprise. It’s history in the making... I wish I had a camera.

“What!” she says, and I laugh.

Actually, I’m glad I haven’t got that camera: you take a photo and you forget the image, or you forget the moment you took it. It’d only end up as one of the million silly snaps all couples take of each other. I realise I’m lucky to have that image of her face as it was when she first heard the abrupt ending of I Want You (She’s So Heavy), along with every other detail, every rustle and crackle of that record, imprinted forever on my memory.

Or at least I was – lucky, I mean. I was never able to listen to that track again without remembering that evening, the happiness and cosiness of it, and Fon’s face. That was good for a long time but then I couldn’t listen to it without remembering the innocence we still had of each other and of the difficulties and heartbreaks that were yet to come.

The last time I listened to Abbey Road must have been a few weeks before I moved out of the flat, which itself was a few months after Fon left. If our relationship just before that time sounded like the swirling, maddening coda of I Want You (She’s So Heavy), her leaving sounded like the sudden silence as the track ended and the needle lifted off the spinning vinyl. I don’t even have the album anymore.

Wednesday, June 15, 2005

The intro and the outro

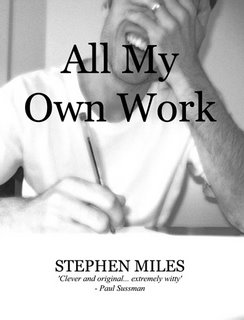

A few years ago my novel All My Own Work was named a winner of The Leonard Sankey Awards for New Talent in Fiction. Billed at the time as one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the UK, it promised a cheque for £10,000, a place on a top-quality writing course and the guidance of a professional editor. However, as well reported in the media at the time, I was controversially stripped of the award and All My Own Work was never published. The Sankey awards also seemed to be placed on indefinite hold following the fracas, but that's another story.

In dire need of money in the months that followed, I decided to write my side of the story - i.e. not the story originally told in All My Own Work but the true story of how I came to write the book, win and then lose the Sankey prize, and the parts played in all of this by various people including my estranged Thai wife Fon and my friends Vince, Eric, Alastair and George. However, my attempts to write the book were frustrated by a severe case of writer's block, so I enlisted the help of an old writer “friend”, who shall remain nameless, to write the book with me.

All went swimmingly for several months, and by early 2004 we had a finished manuscript called Me and My Big Ideas. However, to add irony to injury, my so-called writer so-called friend then tried to pass off our manuscript of my memoir as his own novel, which he retitled, somewhat confusingly, All My Own Work. By some legal miracle he managed to control the rights to the book for the best part of a year, during which time he entered it into the Publish And Be Damned / UKA Press 'Search for a Great Read' competition, the first prize for which was publication by the small press people of “his” “novel”. The book was one of six shortlisted for the prize, but I now find myself in the increasingly ironic position of saying it was fortunate that All My Own Work did not win.

Now, after extensive assertion of my moral rights, I have gained control of the book, subject to certain conditions, namely that while my “writer” “friend” does not own my story, he retains the rights to the actual text he wrote, so I am now having to rewrite the book in order not to breach his copyright - his copyright in my life!

Anyway, these ludicrous wranglings are immaterial in the grand scheme of things. My top priority now is to finally give voice to my side of the story of All My Own Work and the Sankey competition. However, having lost a lot of faith in the publishing industry as a result of this entire palaver, I’ve decided my best course of action is to post my manuscript to the web chapter by chapter as I revise it. I’m just finishing off the first chapters now and these should be ready in the next few days. After that, if my present rate of work is anything to go by, I should be able to post two or three chapters every week. Ultimately this will build into a complete book, and if it's the last thing I do, it really will be all my own work!

In dire need of money in the months that followed, I decided to write my side of the story - i.e. not the story originally told in All My Own Work but the true story of how I came to write the book, win and then lose the Sankey prize, and the parts played in all of this by various people including my estranged Thai wife Fon and my friends Vince, Eric, Alastair and George. However, my attempts to write the book were frustrated by a severe case of writer's block, so I enlisted the help of an old writer “friend”, who shall remain nameless, to write the book with me.

All went swimmingly for several months, and by early 2004 we had a finished manuscript called Me and My Big Ideas. However, to add irony to injury, my so-called writer so-called friend then tried to pass off our manuscript of my memoir as his own novel, which he retitled, somewhat confusingly, All My Own Work. By some legal miracle he managed to control the rights to the book for the best part of a year, during which time he entered it into the Publish And Be Damned / UKA Press 'Search for a Great Read' competition, the first prize for which was publication by the small press people of “his” “novel”. The book was one of six shortlisted for the prize, but I now find myself in the increasingly ironic position of saying it was fortunate that All My Own Work did not win.

Now, after extensive assertion of my moral rights, I have gained control of the book, subject to certain conditions, namely that while my “writer” “friend” does not own my story, he retains the rights to the actual text he wrote, so I am now having to rewrite the book in order not to breach his copyright - his copyright in my life!

Anyway, these ludicrous wranglings are immaterial in the grand scheme of things. My top priority now is to finally give voice to my side of the story of All My Own Work and the Sankey competition. However, having lost a lot of faith in the publishing industry as a result of this entire palaver, I’ve decided my best course of action is to post my manuscript to the web chapter by chapter as I revise it. I’m just finishing off the first chapters now and these should be ready in the next few days. After that, if my present rate of work is anything to go by, I should be able to post two or three chapters every week. Ultimately this will build into a complete book, and if it's the last thing I do, it really will be all my own work!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)