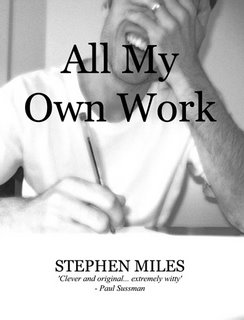

A belated update to the blog to say that my book is now available direct from publisher Thoughtcat's Lulu shop at only £7.50* plus p&p. This is down from the original price of £10.99.

And if you don't think £7.50 is reasonable, Thoughtcat is even offering a limited supply of copies for 'pay what you like', inclusive of p&p.

Impoverishedly,

Steve

* Due to a technical problem the price of the book is in US$ so the price in GBP is showing as a conversion. Therefore you may pay a few pence more than £7.50, but only a few pence (currently £7.54). You may ask why we don't just advertise the book for £7.54. The answer is it would just look silly.

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

All My Own Work in the local paper

I'm 'delighted' to hear from Thoughtcat that venerable local organ The Richmond & Twickenham Times reports this week on the story of All My Own Work's publication, under the headline 'Disgraced author's new offering'. There doesn't appear to be an online version of the story as yet, but Richard (or rather 'Ron' as the Times has it!) has done an excellent cut'n'paste job with the press cutting (are you sure we didn't work at the same company back in the nineties, Rich?) and has updated the 'Thought Cat' site with the (offending) article. Meanwhile, I'm going back to my sticky rice...

In disgrace,

Steve

In disgrace,

Steve

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Chapters Eight and Nine

A Christmas treat! Finally, as promised several aeons ago, here are some more sample chapters from the book. I've decided to skip the rest of Part 1 which was partially previewed here last year and go straight into Part 2, which (all bar the shouting) begins with...

Chapter Eight

When I left school and, shortly afterwards, home, all I wanted to do with my life was write. For years I lived in bedsits and flatshares and other living spaces as economical as those compound nouns, moving around from town to town and job to job, rarely caring what I did or how I lived as long as I had a big enough room for a bed, a desk and a chair, and enough cash for my rent, food and cigarettes. I wasn't a career kind of guy; the only career I was interested in was writing, and that wasn't something you made a career of, it was just something you did. Mine was a simple, rather naive lifestyle, and even now I sometimes catch myself feeling nostalgic for it, but it really wasn't as romantic as it might sound: the rooms were rank, the jobs were dreary and the hours, whether I was writing or not, were long and heavy.

It wouldn't've been so bad, perhaps, if I'd been the sort of writer whom women found irresistible, but I wasn't, and never will be: without wishing to go into great detail about my love-life before I met Fon (the details of it after I met her are, I should think, quite enough), it was, I'd say, about average, even taking into account a later start in these matters than I would have liked and some very lean periods where the closest I got to swapping bodily fluids with anyone was using the communal bath after a fellow tenant. As you might expect of a lonesome writer- manqué who generally preferred to spend the evenings indoors with a bottle of vino and a Beatles album than trying his luck in a bar, love and sex for me were far higher on quality than on quantity, boiling down to maybe half a dozen sporadic affairs which lasted between a couple of months and a couple of years, each both ordinary and wonderful in their own ways and all of them ending about as naturally and amicably as is possible between men and women.

If there was one thing which got me through those years it was a book – The Medusa Frequency, a novel by Russell Hoban, an American-born writer long since expatriated to these shores. I've often thought of it as my Desert Island Discs book, although whether I'll actually end up on the show is a matter still under discussion at the BBC. Apart from my pendant of Luan Po Tuad, this was the only other treasured possession I salvaged from my home before I ran away.

I was in my late teens when the book came out. I first read about it in the Literary Review, a slightly pretentious magazine I subscribed to in those days in the belief it was what you did if you were serious about becoming a writer. The review was what you might call enthusiastic, featuring a photo of the author – a short, round, sixty-ish man with a white beard and no moustache – captioned HOBAN: IS HE THE GREATEST WRITER IN THE WORLD? I wasn't used to books doing to me what this one did; I'd read a few great ones at school and college – The Lord of the Flies, Great Expectations, Heart of Darkness – but there was still something black-and-white to me about those classics. The Medusa Frequency was the first book I read which seemed to have been written in colour. No novel before or since has inspired me in the fundamental and profound way that this one did: apart from being beautifully written, it was concerned with what were already the two central issues in my life – writing and relationships. In that order. A decade and a half later, I've lost count of the number of times I've read it, but it does the same thing to me every time: it makes me feel that anything is possible – with regard to writing, anyway. It's more realistic about relationships.

In the book, Herman Orff, a London-based comic-book illustrator and sometime novelist, is trying to overcome his writer's block and get his third novel off the ground. He is obsessed with certain images and stories, chief among them the Greek mythological characters The Kraken – with whom he sits up late at night having 'conversations' at his word-processor – and Orpheus and Eurydice, as well as Vermeer's famous Girl with a Pearl Earring portrait. The Vermeer Girl in turn reminds him of Luise, the love of his life who left him several years before, after he was unfaithful to her. In an attempt to fire his imagination Herman undergoes an unusual brain-zapping technique for boosting creativity (a part I especially liked because it involved being linked up to a Fairlight music computer), following which he starts to hallucinate the dismembered, all-singing, all-storytelling head of Orpheus, which appears to him in the guises of various spherical objects – a football, a cabbage, a rock in the low-tide mud by the Thames. The head tells Herman his story: how he learnt to play the lyre, how he met Eurydice and they fell in love, and how he lost her forever when he looked back while retrieving her from the Underworld. Gradually the reasons for the failure of the love between Orpheus and Eurydice help Herman to understand what went wrong in his own relationship – as Luise puts it, she trusted him with the idea of her, and he lost it.

It's an optimistic story in the sense that Herman resolves his artistic problems and reaches some sort of peace with Luise, but she does end up lost to him forever. I don't think this is giving much away – I mean, it is the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, after all. Given this, as well as the ambiguity of whether or not Herman ever finds the third novel he was looking for, I suppose it's ironic that I should feel that this of all books has made me feel 'anything is possible'; it's not something I've really thought about until now. Anyway, throughout these lean years I used to go on long walks down by the Thames in Richmond, a picturesque town in Surrey I've always loved, and at times of particular anxiety, loneliness or plain and simple writer's block, I would go hunting along the towpath there for the Head of Orpheus. As you might expect, I had a number of fruitless searches before I found it.

It was February, just after dusk, the sky the rich, deep purple of a ripe black eye, the streetlamps buzzing their warm yellow in the air and glistening off the wet pavements. The tall young German who ran the café in one of the arches under Richmond Bridge was cleaning up and getting ready to close, the electric lights glowing yellow behind steamy windows. I looked over at the backs of the restaurants and hotels facing the river and thought again how they reminded me of Paris – they always had done, in fact, even before I'd visited the city. I walked on past the landmarks I knew by heart, the benches under the blossom trees, the expensive restaurant that had risen up a couple of years back from the ashes of a burnt-down pizza shack, and the kiosk, long fallen into disrepair, its peeling sign still saying REFRESHMENTS. Opposite the kiosk was a jetty used by the local boating people, and on this occasion I noticed floating beside it something I'd never seen before.

The river was running fast that evening, like a fully-opened bath tap, and bobbing in it was a dirty white spherical buoy, a bit larger than a football. Tethered fast to the jetty, it moved up and down a little in the current but it stayed more or less in that spot. As I watched, it rolled up out of the river and two round, white, shiny discs appeared on it in exactly the place a pair of eyes would be on a human face. I looked around and quickly realised the eyes were no more than the reflections of two streetlamps on either side of me, but I couldn't ignore the idea that the buoy was in fact my very own Head of Orpheus. I flashed a sad smile to myself at the thought of the book, at how good it and its author were and how useless – and, frankly, fey – I was. Why didn't things like that happen in real life? Why couldn't the real Head of Orpheus appear to me and help me write my Difficult Third Novel, or even my Difficult First Novel for that matter? God, you're hopeless, I thought (about myself, I mean, not God; I didn't have a problem with Him, it was me who had to sort my life out) – here you are trudging Lowry-like along the river again on another cold evening, always giving yourself some path to walk down, always looking for something that isn't there… the Head of Orpheus is in a book, it's a product of someone's imagination. Hoban – and, it should be said, the Head of Orpheus itself – would doubtless say that that doesn't make it less real, but, you know, it's been done. Get a life, Miles – get your own life!

I stared at the Buoy of Orpheus for several minutes, hanging on to the absurd hope that it would say something, that something, anything out of the ordinary would happen to get me out of the rut I was in. It was a crucial moment – things could surely only get worse if I found myself alone by the river willing a buoy to speak to me and nothing happened. At last, to my relief, a voice spoke to my mind. 'What are you after?' it said.

'Are you talking to me?' I replied, with my mind.

'I don't see anybody else standing around,' it said.

The voice was gruff and whatever it was was talking under its breath, like the bloke with the year-round bobble hat and hands like raw rump steaks who sold the Standard in Richmond high street. I looked around; I appeared to be alone.

'Is this the buoy speaking?' I said.

'If you like,' said the buoy. 'As I said, what are you after?'

'Nothing,' I said, suddenly even more self-conscious than usual.

'Liar,' it said. 'You're looking for answers.'

'Who isn't?' I said.

'Don't come the philosopher,' it said. 'Tell me what you're looking for.'

I thought hard. How was I supposed to answer the question? Now that I had the chance of asking, I had no idea what to say. The whole thing felt ridiculous. 'I don't know,' I sighed. 'Nothing... everything.'

'Hmm,' said the buoy. 'Tricky one. Well, to be honest, I think you need to clarify your question a little and come back when you've worked it out, hm?'

'Can't you just tell me something to be getting along with?' I said. 'Anything will do.'

'You're easily pleased, aren't you?' said the buoy.

'I don't know,' I said again. 'I guess.'

'I think I know what's going on here,' said the buoy, suggesting that if it had a chin it would be scratching it. 'You're bored, uninspired, maybe even a little desperate, no? You think you've come to the limits of yourself, and you want some reassurance that there's more to you than meets the eye at the moment.'

'Yes,' I said. 'That's it. That's very perceptive.'

'Well,' it sighed, 'there's not much I can say, really... just hang on in there, keep an eye out and let it happen. It'll come to you.'

'What'll come to me?' I said. 'A story? A woman?'

'Probably,' it said.

'Which?' I said. 'When? How?'

'Just keep an eye out. It'll be there. That's all I can say.'

'Is that it? Is that the answer I was looking for?'

'What did you expect,' said the buoy, 'a miracle? Sorry, I'm a bit short on those at the moment. Should have some in with the Friday delivery. Put your name down for one if you like.'

'Oh, go fish,' I said.

'That's an idea,' said the buoy, and promptly vanished under a particularly strong current.

I expected the experience to depress me even more, but the next day I woke up in decisive mood. Bugger the idea of waiting for something to happen, I thought: if writing and relationships were beyond my control, I should at least find a job I enjoyed and a decent place to live. Tipping a cockroach out of the window with a copy of the Media Guardian, I noticed an advert for a vacancy with a press cuttings agency near London Bridge; I'd never thought about that sort of work before, but I found myself applying for it anyway. I was invited for an interview, did a couple of tests to see how fast I could read and cut up newspaper articles, and within a week I was doing it for a living. The work was repetitive but easy, and the people and atmosphere were the best I'd known in any job: we were all in our twenties, we could wear what we liked, and, as long as we got the job done, we could work whatever hours we wanted. To cap it all, the firm rewarded hard (for which read 'dogged') work with regular pay rises, and after a year or so, for the first time in my life I was both doing a job I liked and earning enough to raise a mortgage.

When people asked me what working for a press cuttings agency involved, I'd tell them it was like scrap-books for grown-ups, and even that was stretching it. A client, normally a company although sometimes an individual, is looking for 'search terms' – mentions of companies (themselves, their competitors, firms they invest in, their own clients) or subjects (telecommunications, instant coffee, depression, condoms) in various print contexts. These include the national press ( The Guardian, The Independent), the regional press (The Yate & Sodbury Gazette, The Framley Examiner), general magazines (Esquire, Cosmopolitan), trade magazines (The Grocer, Capitalist Bastard Weekly ), and, these days, although not so much when I first joined the firm, the internet and news agencies (FT.com, Reuters). A 'reader' scans through these publications for the desired mentions, and when one is found, he cuts out the whole article it appeared in, arranges it neatly with scissors and glue onto A4 paper, photocopies it, puts it in the client's tray, and at the end of the day sends it out to the client in a plain brown envelope. Of all the jobs I ever had, never was there one with a more (unintentionally) ironic job title than 'reader': the stack of publications you had to 'read' in a day for the thousands of search terms required by the hundreds of clients meant you never had time to actually read anything. I imagine it was slightly more difficult than being a judge of a literary award.

I was slicing up a copy of Time Out one afternoon (something I'd often done in an amateur capacity, but to be paid for it was sublime) when I came across a tiny advert for a one-bedroomed flat in Twickenham, a suburb in south-west London that probably wouldn't be known about at all outside the immediate area were it not for the international rugby ground. The flat turned out to be above a flower shop in a high street on the less exclusive side of Richmond Bridge, literally just across the water from my favourite town, and about ten minutes' walk from the buoy I was still consulting, oracle-like, on a regular basis, even if its answers were mostly the same every time. Whimsical as it may be, I couldn't rid myself of the idea that this was somehow meant to have happened. Although the flat was draughty, damp, uncarpeted, noisy and dusty and had a boiler that clanked for England and a short lease, it was also very cheap – these were the mid-nineties, before London property prices spiralled out of the reach of people like me – and I knew from the moment I first viewed it that it would be mine: my mortgage would come through, there would be no other bidders and no delays; the flat had my name on it. I could settle down there and, pushing thirty as I was, finally begin to begin my life.

Yeah, I was happy there for a long time... letting it get repossessed was probably the second stupidest thing I ever did.

Chapter Nine

Another reason I fell in love with that flat was that it made me nostalgic for growing up above Mum and Dad's grocery shop, way over on the other side of Surrey. If I close my eyes and think back to my childhood, I am invariably sitting in the flat after school, watching TV and eating toast, alone but for the muffled conversation and laughter of the customers and staff filtering warmly up from below. That said, the first-floor position was pretty much where the local comparisons ended: although my neighbouring flats were similar in that they were generally occupied by the white, middle-class and ethnically English, the local Twickenham shops were far more cosmopolitan than those I'd known as a child: here I could have my hair cut by a Greek Cypriot, buy my newspaper from a Sri Lankan, get my groceries from a French deli and fresh-baked croissants from a Lebanese café. At times it didn't feel like a suburb at all, but more like a budget Soho.

Something else that was good about living on a high street was that the window was a permanent entertainment. I'd spend hours sitting there watching all of life walking, running, driving, cycling, shuffling, muttering, snogging, yelling and screaming past. For a single man and a struggling writer, that front window was a panacea, providing distraction when I was bored, inspiration when I was blocked and company when I was lonely. And even when the street quietened down in the evenings, it seamlessly passed on the baton of activity to the restaurant directly opposite my flat.

When I first moved in, the restaurant was an Italian called Mamma's. I used to do my writing at the dining table I'd parked right by the lounge window, and from there, on slow evenings for both of us, I'd sit and watch the owner, a bone-thin man with a lugubrious grey moustache, while away his life at the bar smoking cigarettes and drinking red wine. When the weather was cold and Mamma's was busy, the windows would steam up and all you could see were the flickerings of candles on tables like a misty garden filled with dewy blooms of light. Sadly, the food itself was less inspiring, as I found out on the only occasion I ate there, but even if it wasn't a great restaurant, Mamma's was without a doubt the nicest feature of my flat, and its warmth kept me going through three or four years of living alone – a part-time, on-off, live-out girlfriend notwithstanding – and the eternal struggle to write.

One evening I came home from work to find Mamma's windows whitewashed and a notice up saying LEASE FOR SALE. I remember feeling as if I'd been dumped by a lover – and then reflecting on the sad fact that Mamma's was as close as I'd been to sex in ages (the part-time girlfriend having by now resigned entirely). It was winter, and the months that passed while the landlord tried to find a new tenant were as bleak as any I'd ever known – even in my New Malden period, where McDonalds was as exotic as anything got. Give me a naff restaurant that's open for business over whitewashed windows any day of the week.

When the restaurant finally reopened the following spring, the whole street seemed to breathe a sigh of relief. Given the variety of shops and nationalities in the area, I suppose I shouldn't have been as surprised as I was when Mamma's was reborn as a Thai restaurant, but this was still slightly before Thai places started opening everywhere, and in all honesty I'd never given a second thought to the country. I'd never eaten Thai food at that time, couldn't name a single dish, and if anyone had asked me even to name Thailand's capital or find it on a map, I think I'd've been lost. Geography, beyond France anyway, had never been much discussed at the Miles family dinner table; in retrospect, what passed for my appreciation of Thai history and culture had been formed on languid Sunday afternoons in distant, hazy childhood watching Yul Brynner twirl Deborah Kerr around the floor in The King and I, as well as Walt Disney's bloody Siamese cats duet, and in both cases I wasn't even conscious that Thailand and Siam were the same thing. The Thai Garden, as the restaurant was called, was therefore exotic, but it was exotica tinged with confusion – a little like a certain relationship I was to have some time later.

As I watched the curious new sign with its curly lettering replace the old Mamma's hoarding, I wondered what the food would be like and how long the place would last. To my surprise, it was soon full every night, and when I went down with Tim, an old mate, and a couple of friends from work one evening, we found from the quality of the cooking that the novelty factor was by no means the only attraction. Even better, the customers and staff all seemed young and alive – and playful. I was at home cooking dinner one night, and glancing idly out the window (the cooker was right next to it) I saw a whole table of people looking up, waving and smiling. I peered down the street in both directions to see what they might be looking at, but when I looked back at them I realised it was me they were waving to. I hadn't shaved, the kitchen needed a clean, and I was wearing a saggy old tee-shirt, but I smiled it off and raised my glass to them – earning myself a rapturous round of silent applause into the bargain.

After that night, I would be waved at by someone in the restaurant at least once a week. Even if the wavers and I were complete strangers, it was reassuring to know I wasn't just a figment of my own imagination, as living alone and writing for hours on end – even on a high street – often made me feel. My existence in three dimensions was officially confirmed when the staff began waving to me every evening. A particularly bold waitress with a hair-grip of the sort that David Beckham would later make famous started the routine, and before long they were all at it. The waitress would generally appear at the window at around seven o'clock, just as the staff rose from their meal and the restaurant opened for the evening service, and it got to the point where if I hadn't had a wave by five past, I'd be on the floor having a full-blown identity crisis. But this was rare, and they were always glad to see me when I ventured out from my kitchen and into the restaurant and, by implication, the real world.

Over the following year I developed something of an acquaintance with the hairgripped waitress, whose name was Aoy, and on one occasion I even asked her out for a drink, although it came to nothing because she was due to fly back to Thailand for three months the next day. As excuses went, it was better than many I'd heard, but my disappointment must have shown because she promised me she'd tell her replacement, an old friend from her home town, to make sure I was waved at regularly in her absence.

Aoy's promise cheered me up, but I forgot all about it until a few weeks later. It was a Sunday morning in July, just gone eleven, I was sitting in the lounge reading the papers and the Thai Gardeners were starting to turn up for the lunch service. I was vaguely aware that there was someone new among them, but as staff came and went fairly regularly I didn't pay much attention to her – until she came and sat in the front window and made a call on her mobile phone, that is.

I remember the moment well: a gentle breeze from the open window, a cup of filter coffee to hand, and on the stereo one of my favourite Sunday-morning records, John McLaughlin's Time Remembered. When I die and they cut me open, they'll find those exquisite acoustic guitar renditions of Bill Evans's jazz piano pieces running right through me like the word BRIGHTON in a stick of rock; I suppose on that basis it doesn't matter that that's another album I no longer own. The CD sleeve is imprinted on my mind equally vividly: a simple blue-toned monochrome photo of McLaughlin standing over a Spanish guitar laid on the lid of a grand piano. You couldn't see much of the room he was in, but the windows behind him were suggestive of the sort of living room where you could comfortably spend your life. The wood of both guitar and piano had been glazed and polished, so the reflections of the windows rhymed in the glassy surfaces of both instruments, soft but bright. The music always sounded to me like the way the light fell on that wood, and in that hot Sunday morning moment the new girl's cool face looked to me like that music.

(c) Stephen Miles 2006

To buy a copy of All My Own Work please go to www.thoughtcat.com

Chapter Eight

When I left school and, shortly afterwards, home, all I wanted to do with my life was write. For years I lived in bedsits and flatshares and other living spaces as economical as those compound nouns, moving around from town to town and job to job, rarely caring what I did or how I lived as long as I had a big enough room for a bed, a desk and a chair, and enough cash for my rent, food and cigarettes. I wasn't a career kind of guy; the only career I was interested in was writing, and that wasn't something you made a career of, it was just something you did. Mine was a simple, rather naive lifestyle, and even now I sometimes catch myself feeling nostalgic for it, but it really wasn't as romantic as it might sound: the rooms were rank, the jobs were dreary and the hours, whether I was writing or not, were long and heavy.

It wouldn't've been so bad, perhaps, if I'd been the sort of writer whom women found irresistible, but I wasn't, and never will be: without wishing to go into great detail about my love-life before I met Fon (the details of it after I met her are, I should think, quite enough), it was, I'd say, about average, even taking into account a later start in these matters than I would have liked and some very lean periods where the closest I got to swapping bodily fluids with anyone was using the communal bath after a fellow tenant. As you might expect of a lonesome writer- manqué who generally preferred to spend the evenings indoors with a bottle of vino and a Beatles album than trying his luck in a bar, love and sex for me were far higher on quality than on quantity, boiling down to maybe half a dozen sporadic affairs which lasted between a couple of months and a couple of years, each both ordinary and wonderful in their own ways and all of them ending about as naturally and amicably as is possible between men and women.

If there was one thing which got me through those years it was a book – The Medusa Frequency, a novel by Russell Hoban, an American-born writer long since expatriated to these shores. I've often thought of it as my Desert Island Discs book, although whether I'll actually end up on the show is a matter still under discussion at the BBC. Apart from my pendant of Luan Po Tuad, this was the only other treasured possession I salvaged from my home before I ran away.

I was in my late teens when the book came out. I first read about it in the Literary Review, a slightly pretentious magazine I subscribed to in those days in the belief it was what you did if you were serious about becoming a writer. The review was what you might call enthusiastic, featuring a photo of the author – a short, round, sixty-ish man with a white beard and no moustache – captioned HOBAN: IS HE THE GREATEST WRITER IN THE WORLD? I wasn't used to books doing to me what this one did; I'd read a few great ones at school and college – The Lord of the Flies, Great Expectations, Heart of Darkness – but there was still something black-and-white to me about those classics. The Medusa Frequency was the first book I read which seemed to have been written in colour. No novel before or since has inspired me in the fundamental and profound way that this one did: apart from being beautifully written, it was concerned with what were already the two central issues in my life – writing and relationships. In that order. A decade and a half later, I've lost count of the number of times I've read it, but it does the same thing to me every time: it makes me feel that anything is possible – with regard to writing, anyway. It's more realistic about relationships.

In the book, Herman Orff, a London-based comic-book illustrator and sometime novelist, is trying to overcome his writer's block and get his third novel off the ground. He is obsessed with certain images and stories, chief among them the Greek mythological characters The Kraken – with whom he sits up late at night having 'conversations' at his word-processor – and Orpheus and Eurydice, as well as Vermeer's famous Girl with a Pearl Earring portrait. The Vermeer Girl in turn reminds him of Luise, the love of his life who left him several years before, after he was unfaithful to her. In an attempt to fire his imagination Herman undergoes an unusual brain-zapping technique for boosting creativity (a part I especially liked because it involved being linked up to a Fairlight music computer), following which he starts to hallucinate the dismembered, all-singing, all-storytelling head of Orpheus, which appears to him in the guises of various spherical objects – a football, a cabbage, a rock in the low-tide mud by the Thames. The head tells Herman his story: how he learnt to play the lyre, how he met Eurydice and they fell in love, and how he lost her forever when he looked back while retrieving her from the Underworld. Gradually the reasons for the failure of the love between Orpheus and Eurydice help Herman to understand what went wrong in his own relationship – as Luise puts it, she trusted him with the idea of her, and he lost it.

It's an optimistic story in the sense that Herman resolves his artistic problems and reaches some sort of peace with Luise, but she does end up lost to him forever. I don't think this is giving much away – I mean, it is the story of Orpheus and Eurydice, after all. Given this, as well as the ambiguity of whether or not Herman ever finds the third novel he was looking for, I suppose it's ironic that I should feel that this of all books has made me feel 'anything is possible'; it's not something I've really thought about until now. Anyway, throughout these lean years I used to go on long walks down by the Thames in Richmond, a picturesque town in Surrey I've always loved, and at times of particular anxiety, loneliness or plain and simple writer's block, I would go hunting along the towpath there for the Head of Orpheus. As you might expect, I had a number of fruitless searches before I found it.

It was February, just after dusk, the sky the rich, deep purple of a ripe black eye, the streetlamps buzzing their warm yellow in the air and glistening off the wet pavements. The tall young German who ran the café in one of the arches under Richmond Bridge was cleaning up and getting ready to close, the electric lights glowing yellow behind steamy windows. I looked over at the backs of the restaurants and hotels facing the river and thought again how they reminded me of Paris – they always had done, in fact, even before I'd visited the city. I walked on past the landmarks I knew by heart, the benches under the blossom trees, the expensive restaurant that had risen up a couple of years back from the ashes of a burnt-down pizza shack, and the kiosk, long fallen into disrepair, its peeling sign still saying REFRESHMENTS. Opposite the kiosk was a jetty used by the local boating people, and on this occasion I noticed floating beside it something I'd never seen before.

The river was running fast that evening, like a fully-opened bath tap, and bobbing in it was a dirty white spherical buoy, a bit larger than a football. Tethered fast to the jetty, it moved up and down a little in the current but it stayed more or less in that spot. As I watched, it rolled up out of the river and two round, white, shiny discs appeared on it in exactly the place a pair of eyes would be on a human face. I looked around and quickly realised the eyes were no more than the reflections of two streetlamps on either side of me, but I couldn't ignore the idea that the buoy was in fact my very own Head of Orpheus. I flashed a sad smile to myself at the thought of the book, at how good it and its author were and how useless – and, frankly, fey – I was. Why didn't things like that happen in real life? Why couldn't the real Head of Orpheus appear to me and help me write my Difficult Third Novel, or even my Difficult First Novel for that matter? God, you're hopeless, I thought (about myself, I mean, not God; I didn't have a problem with Him, it was me who had to sort my life out) – here you are trudging Lowry-like along the river again on another cold evening, always giving yourself some path to walk down, always looking for something that isn't there… the Head of Orpheus is in a book, it's a product of someone's imagination. Hoban – and, it should be said, the Head of Orpheus itself – would doubtless say that that doesn't make it less real, but, you know, it's been done. Get a life, Miles – get your own life!

I stared at the Buoy of Orpheus for several minutes, hanging on to the absurd hope that it would say something, that something, anything out of the ordinary would happen to get me out of the rut I was in. It was a crucial moment – things could surely only get worse if I found myself alone by the river willing a buoy to speak to me and nothing happened. At last, to my relief, a voice spoke to my mind. 'What are you after?' it said.

'Are you talking to me?' I replied, with my mind.

'I don't see anybody else standing around,' it said.

The voice was gruff and whatever it was was talking under its breath, like the bloke with the year-round bobble hat and hands like raw rump steaks who sold the Standard in Richmond high street. I looked around; I appeared to be alone.

'Is this the buoy speaking?' I said.

'If you like,' said the buoy. 'As I said, what are you after?'

'Nothing,' I said, suddenly even more self-conscious than usual.

'Liar,' it said. 'You're looking for answers.'

'Who isn't?' I said.

'Don't come the philosopher,' it said. 'Tell me what you're looking for.'

I thought hard. How was I supposed to answer the question? Now that I had the chance of asking, I had no idea what to say. The whole thing felt ridiculous. 'I don't know,' I sighed. 'Nothing... everything.'

'Hmm,' said the buoy. 'Tricky one. Well, to be honest, I think you need to clarify your question a little and come back when you've worked it out, hm?'

'Can't you just tell me something to be getting along with?' I said. 'Anything will do.'

'You're easily pleased, aren't you?' said the buoy.

'I don't know,' I said again. 'I guess.'

'I think I know what's going on here,' said the buoy, suggesting that if it had a chin it would be scratching it. 'You're bored, uninspired, maybe even a little desperate, no? You think you've come to the limits of yourself, and you want some reassurance that there's more to you than meets the eye at the moment.'

'Yes,' I said. 'That's it. That's very perceptive.'

'Well,' it sighed, 'there's not much I can say, really... just hang on in there, keep an eye out and let it happen. It'll come to you.'

'What'll come to me?' I said. 'A story? A woman?'

'Probably,' it said.

'Which?' I said. 'When? How?'

'Just keep an eye out. It'll be there. That's all I can say.'

'Is that it? Is that the answer I was looking for?'

'What did you expect,' said the buoy, 'a miracle? Sorry, I'm a bit short on those at the moment. Should have some in with the Friday delivery. Put your name down for one if you like.'

'Oh, go fish,' I said.

'That's an idea,' said the buoy, and promptly vanished under a particularly strong current.

I expected the experience to depress me even more, but the next day I woke up in decisive mood. Bugger the idea of waiting for something to happen, I thought: if writing and relationships were beyond my control, I should at least find a job I enjoyed and a decent place to live. Tipping a cockroach out of the window with a copy of the Media Guardian, I noticed an advert for a vacancy with a press cuttings agency near London Bridge; I'd never thought about that sort of work before, but I found myself applying for it anyway. I was invited for an interview, did a couple of tests to see how fast I could read and cut up newspaper articles, and within a week I was doing it for a living. The work was repetitive but easy, and the people and atmosphere were the best I'd known in any job: we were all in our twenties, we could wear what we liked, and, as long as we got the job done, we could work whatever hours we wanted. To cap it all, the firm rewarded hard (for which read 'dogged') work with regular pay rises, and after a year or so, for the first time in my life I was both doing a job I liked and earning enough to raise a mortgage.

When people asked me what working for a press cuttings agency involved, I'd tell them it was like scrap-books for grown-ups, and even that was stretching it. A client, normally a company although sometimes an individual, is looking for 'search terms' – mentions of companies (themselves, their competitors, firms they invest in, their own clients) or subjects (telecommunications, instant coffee, depression, condoms) in various print contexts. These include the national press ( The Guardian, The Independent), the regional press (The Yate & Sodbury Gazette, The Framley Examiner), general magazines (Esquire, Cosmopolitan), trade magazines (The Grocer, Capitalist Bastard Weekly ), and, these days, although not so much when I first joined the firm, the internet and news agencies (FT.com, Reuters). A 'reader' scans through these publications for the desired mentions, and when one is found, he cuts out the whole article it appeared in, arranges it neatly with scissors and glue onto A4 paper, photocopies it, puts it in the client's tray, and at the end of the day sends it out to the client in a plain brown envelope. Of all the jobs I ever had, never was there one with a more (unintentionally) ironic job title than 'reader': the stack of publications you had to 'read' in a day for the thousands of search terms required by the hundreds of clients meant you never had time to actually read anything. I imagine it was slightly more difficult than being a judge of a literary award.

I was slicing up a copy of Time Out one afternoon (something I'd often done in an amateur capacity, but to be paid for it was sublime) when I came across a tiny advert for a one-bedroomed flat in Twickenham, a suburb in south-west London that probably wouldn't be known about at all outside the immediate area were it not for the international rugby ground. The flat turned out to be above a flower shop in a high street on the less exclusive side of Richmond Bridge, literally just across the water from my favourite town, and about ten minutes' walk from the buoy I was still consulting, oracle-like, on a regular basis, even if its answers were mostly the same every time. Whimsical as it may be, I couldn't rid myself of the idea that this was somehow meant to have happened. Although the flat was draughty, damp, uncarpeted, noisy and dusty and had a boiler that clanked for England and a short lease, it was also very cheap – these were the mid-nineties, before London property prices spiralled out of the reach of people like me – and I knew from the moment I first viewed it that it would be mine: my mortgage would come through, there would be no other bidders and no delays; the flat had my name on it. I could settle down there and, pushing thirty as I was, finally begin to begin my life.

Yeah, I was happy there for a long time... letting it get repossessed was probably the second stupidest thing I ever did.

Chapter Nine

Another reason I fell in love with that flat was that it made me nostalgic for growing up above Mum and Dad's grocery shop, way over on the other side of Surrey. If I close my eyes and think back to my childhood, I am invariably sitting in the flat after school, watching TV and eating toast, alone but for the muffled conversation and laughter of the customers and staff filtering warmly up from below. That said, the first-floor position was pretty much where the local comparisons ended: although my neighbouring flats were similar in that they were generally occupied by the white, middle-class and ethnically English, the local Twickenham shops were far more cosmopolitan than those I'd known as a child: here I could have my hair cut by a Greek Cypriot, buy my newspaper from a Sri Lankan, get my groceries from a French deli and fresh-baked croissants from a Lebanese café. At times it didn't feel like a suburb at all, but more like a budget Soho.

Something else that was good about living on a high street was that the window was a permanent entertainment. I'd spend hours sitting there watching all of life walking, running, driving, cycling, shuffling, muttering, snogging, yelling and screaming past. For a single man and a struggling writer, that front window was a panacea, providing distraction when I was bored, inspiration when I was blocked and company when I was lonely. And even when the street quietened down in the evenings, it seamlessly passed on the baton of activity to the restaurant directly opposite my flat.

When I first moved in, the restaurant was an Italian called Mamma's. I used to do my writing at the dining table I'd parked right by the lounge window, and from there, on slow evenings for both of us, I'd sit and watch the owner, a bone-thin man with a lugubrious grey moustache, while away his life at the bar smoking cigarettes and drinking red wine. When the weather was cold and Mamma's was busy, the windows would steam up and all you could see were the flickerings of candles on tables like a misty garden filled with dewy blooms of light. Sadly, the food itself was less inspiring, as I found out on the only occasion I ate there, but even if it wasn't a great restaurant, Mamma's was without a doubt the nicest feature of my flat, and its warmth kept me going through three or four years of living alone – a part-time, on-off, live-out girlfriend notwithstanding – and the eternal struggle to write.

One evening I came home from work to find Mamma's windows whitewashed and a notice up saying LEASE FOR SALE. I remember feeling as if I'd been dumped by a lover – and then reflecting on the sad fact that Mamma's was as close as I'd been to sex in ages (the part-time girlfriend having by now resigned entirely). It was winter, and the months that passed while the landlord tried to find a new tenant were as bleak as any I'd ever known – even in my New Malden period, where McDonalds was as exotic as anything got. Give me a naff restaurant that's open for business over whitewashed windows any day of the week.

When the restaurant finally reopened the following spring, the whole street seemed to breathe a sigh of relief. Given the variety of shops and nationalities in the area, I suppose I shouldn't have been as surprised as I was when Mamma's was reborn as a Thai restaurant, but this was still slightly before Thai places started opening everywhere, and in all honesty I'd never given a second thought to the country. I'd never eaten Thai food at that time, couldn't name a single dish, and if anyone had asked me even to name Thailand's capital or find it on a map, I think I'd've been lost. Geography, beyond France anyway, had never been much discussed at the Miles family dinner table; in retrospect, what passed for my appreciation of Thai history and culture had been formed on languid Sunday afternoons in distant, hazy childhood watching Yul Brynner twirl Deborah Kerr around the floor in The King and I, as well as Walt Disney's bloody Siamese cats duet, and in both cases I wasn't even conscious that Thailand and Siam were the same thing. The Thai Garden, as the restaurant was called, was therefore exotic, but it was exotica tinged with confusion – a little like a certain relationship I was to have some time later.

As I watched the curious new sign with its curly lettering replace the old Mamma's hoarding, I wondered what the food would be like and how long the place would last. To my surprise, it was soon full every night, and when I went down with Tim, an old mate, and a couple of friends from work one evening, we found from the quality of the cooking that the novelty factor was by no means the only attraction. Even better, the customers and staff all seemed young and alive – and playful. I was at home cooking dinner one night, and glancing idly out the window (the cooker was right next to it) I saw a whole table of people looking up, waving and smiling. I peered down the street in both directions to see what they might be looking at, but when I looked back at them I realised it was me they were waving to. I hadn't shaved, the kitchen needed a clean, and I was wearing a saggy old tee-shirt, but I smiled it off and raised my glass to them – earning myself a rapturous round of silent applause into the bargain.

After that night, I would be waved at by someone in the restaurant at least once a week. Even if the wavers and I were complete strangers, it was reassuring to know I wasn't just a figment of my own imagination, as living alone and writing for hours on end – even on a high street – often made me feel. My existence in three dimensions was officially confirmed when the staff began waving to me every evening. A particularly bold waitress with a hair-grip of the sort that David Beckham would later make famous started the routine, and before long they were all at it. The waitress would generally appear at the window at around seven o'clock, just as the staff rose from their meal and the restaurant opened for the evening service, and it got to the point where if I hadn't had a wave by five past, I'd be on the floor having a full-blown identity crisis. But this was rare, and they were always glad to see me when I ventured out from my kitchen and into the restaurant and, by implication, the real world.

Over the following year I developed something of an acquaintance with the hairgripped waitress, whose name was Aoy, and on one occasion I even asked her out for a drink, although it came to nothing because she was due to fly back to Thailand for three months the next day. As excuses went, it was better than many I'd heard, but my disappointment must have shown because she promised me she'd tell her replacement, an old friend from her home town, to make sure I was waved at regularly in her absence.

Aoy's promise cheered me up, but I forgot all about it until a few weeks later. It was a Sunday morning in July, just gone eleven, I was sitting in the lounge reading the papers and the Thai Gardeners were starting to turn up for the lunch service. I was vaguely aware that there was someone new among them, but as staff came and went fairly regularly I didn't pay much attention to her – until she came and sat in the front window and made a call on her mobile phone, that is.

I remember the moment well: a gentle breeze from the open window, a cup of filter coffee to hand, and on the stereo one of my favourite Sunday-morning records, John McLaughlin's Time Remembered. When I die and they cut me open, they'll find those exquisite acoustic guitar renditions of Bill Evans's jazz piano pieces running right through me like the word BRIGHTON in a stick of rock; I suppose on that basis it doesn't matter that that's another album I no longer own. The CD sleeve is imprinted on my mind equally vividly: a simple blue-toned monochrome photo of McLaughlin standing over a Spanish guitar laid on the lid of a grand piano. You couldn't see much of the room he was in, but the windows behind him were suggestive of the sort of living room where you could comfortably spend your life. The wood of both guitar and piano had been glazed and polished, so the reflections of the windows rhymed in the glassy surfaces of both instruments, soft but bright. The music always sounded to me like the way the light fell on that wood, and in that hot Sunday morning moment the new girl's cool face looked to me like that music.

(c) Stephen Miles 2006

To buy a copy of All My Own Work please go to www.thoughtcat.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)